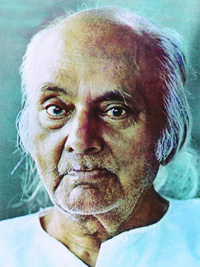

Kazi Nazrul Islam, known as the “Rebel poet” in Bengali literature and the “Bulbul” or Nightingale of Bengali music, was one of the most colourful personalities of undivided Bengal between 1920 and 1940. He may be considered as a pioneer of post-Rabindranath (the Nobel laureate Bengali poet) modernity in Bengali poetry and songs. The new kind of poetry that he wrote made possible the emergence of modernity in Bengali poetry during the 1920s and 1930s. His poems, songs, novels, short stories, plays and political activities expressed strong protest against various forms of oppression- slavery, communalism, feudalism and colonialism- and forced the British government not only to ban many of his books but also to put him in prison. While in prison, Kazi Nazrul lslam once fasted for forty days to register his protest against the tyranny of the government.

Kazi Nazrul Islam was born on May 24, 1899/Joishtho 11, 1306 (Bengali era) in Churulia village, Bordhoman in West Bengal, India. The second of three sons and one daughter, Nazrul lost his father Kazi Fakir Ahmed in 1908 when he was only nine year old. Nazrul’s nickname was “Dukhu” (sorrow) Mia, a name that aptly reflects the hardships and misery of his early years.

His father’s premature death forced him, at the age of ten, to take up teaching at the village school and become the muazzin of the local mosque. Later, Nazrul joined a folk-opera group inspired by his uncle Bazle Karim who himself was well-known for his skill in composing songs in Arabic, Persian and Urdu. As a member of this folk-opera group, the young Nazrul was not only a performer, but began composing poems and songs himself. Nazrul’s involvement with the group was an important formative influence in his literary career.

In 1910, at the age of 11, Nazrul returned to his student life enrolling in class six. But, again, financial difficulties compelled him to leave school after class six, and after a couple of months, Dukhu Mia ended up in a bakery and tea-shop in Asansole. Nazrul submitted to the hard life with characteristic courage. In 1914, Nazrul escaped from the rigours of the tea-shop to re-enter a school in Darirampur village, Trishal in Mymensingh district. Although Nazrul had to change schools two or three more times, he managed to continue up to class ten, and in 1917 he joined the Indian Army when boys of his age were busy preparing for the matriculation pre-test examination.

For almost three years, up to March-April 1920, Nazrul served in the army and was promoted to the rank of Battalion Quarter Master Habildar. Even as a soldier, he continued his literary and musical activities, publishing his first piece” “The Autobiography of a Delinquent” (Saogat, May 1919) and his first poem, “Freedom” (Bongiyo Musalman Shahitto-potrika, in July 1919), in addition to other works composed when he was posted in the Karachi cantonment. What is remarkable is that even when he was in Karachi, he subscribed regularly to the leading contemporary literary periodicals that were published from Calcutta like, Probashi, Bharotborsho, Bharoti, Saogat and others. Nazrul’s literary career can be said to have taken off from the barracks of Karachi.

When after the 1st World War in 1920 the 49th Bengal Regiment was disbanded, Nazrul returned to Kolkata to begin his journalistic and literary life. His poems, essays and novels began to appear regularly in a number of periodicals and within a year or so he became well known not only to the prominent Muslim intellectuals of the time, but was accepted by the Hindu literary establishment in Kolkata as well. In 1921, Nazrul went to Santiniketan to meet Rabindranath Tagore.

Earlier in 1920, the publication of his essay, “Who is responsible for the murder of Muhajirin?” in the new evening daily Nonojug, edited by Nazrul and Muzafar Ahmed, was an expression of Nazru’s new political consciousness and one that made him suspect in the eyes of the police.

In 1921, Nazrul was engaged to be married to Nargis, the niece of a well-known Muslim publisher Ali Akbar Khan, in Doulutpur, Comilla, but on the day of the wedding (18th June, 1921) Nazrul suddenly left the place. This event remains shrouded in mystery. However, many songs and poems reveal the deep wound that this experience inflicted on the young Nazrul and his lingering love for Nargis. Interestingly, during the same trip, Nazrul met Pramila Devi in the house of one Birajasundari Devi in Comilla. Pramila later became his wife.

Later in Kolkata, the same year (1921), Nazrul composed some of his greatest songs and poems of which “Bidrohi” is perhaps the most well-known. The 22-year old poet became on overnight sensation, achieving an unparalleled fame in the history of Bengali literature.

In 1922, Nazrul published a volume of short stories Bethar Daan (The Gift of Sorrow), an anthology of poems Ognibeena, an anthology of essays Jugobani, and a bi-weekly magazine, Dhumketu. A political poem published in Dhumketu in September 1922 led to a police raid on the magazine’s office, a ban on his anthology Jugobani, and one year’s rigorous imprisonment for the poet himself. On April 14, 1923, when Nazrul lslam was transferred from the Alipore jail to the Hooghly jail, he began a fast to protest the mistreatment by a British jail-superintendent. Immediately, Rabindranath Tagore, who had dedicated his musical play, “Boshonto”, to Nazrul, sent a telegram saying: “Give up hunger strike, our literature claims you”, but the telegram was sent back to the sender with the stamp “addressee not found.” Nazrul broke his fast more than a month later and was eventually released from prison in December 1923. A number of poems and songs were composed during the period of imprisonment.

On 25th April, 1924 Kazi Nazrul lslam married Pramila Devi and set up household in Hooghly. An anthology of poems “Bisher Bashi” and an anthology of songs “Bhangar gaan” were published later this year and both volumes were seized by the government. Nazrul soon became actively involved in political activities (1925), joined rallies and meetings, and became a member of the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee. He also played an active role in the formation of a workers and peasants party.

From 1926 when Nazrul settled in Krishnanagar, a new dimension was added to his music. His patriotic and nationalistic songs expanded in scope to articulate the aspirations of the downtrodden classes. His music became truly people-oriented in its appeal. Several songs composed in 1926 and 1927 celebrating fraternity between the Hindus and Muslims and the struggle of the masses, gave rise to what may be called “mass music”. Nazrul’s musical creativity established him not only as an egalitarian composer of “mass music”, but as the innovator of the Bengali Ghazal as well. The two forms, music for the masses and ghazal, exemplified the two aspects of the youthful poet: struggle and love. Nazrul injected a revivifying masculinity and youthfulness into Bengali music. Despite illness, poverty and other hardships Nazrul wrote and composed some of his best songs during his Krishnanagar period. While many others were singing and popularizing his songs in private musical soirees and functions and even making gramophone records, Nazrul himself had yet no direct connection with any gramophone company.

From 1928 to 1932 Nazrul become directly involved with His Master’s Voice Gramophone Company as a lyricist, composer and trainer and a good number of records of Nazrul songs sung by some of the most well-known singers of the time were produced. The newly established Indian Broadcasting Company also enlisted Nazrul as a lyricist and composer and he remained actively involved with several gramophone companies and the Radio till his last working days. Nazrul songs were in great demand on the stage as well. He not only wrote songs for his own plays, but generously provided lyrics and set them to tune for a number of well-known dramatists of the time.

A colourful national reception accorded to Nazrul in 1929 in Kolkata and attended by the scientist Acharjo Prafulla Chandra Ray, Barrister S. Wazed Ali, Subashchandra Bose and others was a demonstration of his rising fame and popularity.

According to a contract with the Megaphone Record Company, many Nazrul lyrics were set to music by others, and it became a practice adopted by the H.M.V. Company subsequently. Devotional songs with an Islamic content (Murshidi, Marfati, etc) were part of the tradition of Bengali folk music. By composing songs dealing with various aspects of Islam (Namaz, Roza, Zakat, etc. ) Nazrul for the first time introduced Islam into the larger mainstream tradition of Bengali music. The first record of Islamic songs by Nazrul was a commercial success and many gramophone companies showed interest in producing these. But an even more significant impact of Nazrul’s “Islamicization” of Bengali music was that it forced a conservative Bengali Muslim community averse to music, to turn a willing ear to listen to Bengali songs. One of the foremost exponents of this new music was the singer Abbasuddin Ahmed. Nazrul also composed a number of notable Shyamasangeet, Bhajan and Kirtan, combining Hindu devotional music. Between 1930 and 1933 Nazrul’s creative energy was devoted mostly to song-writing and music.

In 1933 Nazrul published one of his most important essays entitled “Modem World Literature”. This essay demonstrates his acquaintance with the literature of different languages. In 1934 Nazrul first became associated with the film world. Right at the beginning he played an important role as song and music writer, music director and even actor. Between 1928 and 1935 he published 10 volumes of songs containing over 800 songs of which more than 600 were based on classical ragas, almost 100 were folk tunes after kirtans and some 30 were patriotic and other songs. Thus during the thirties, Nazrul established a firm classical foundation for the Bengali song.

In 1936 the film “Biddapoti” was produced based on Nazrul's recorded play. In the same year Rabindranath Tagore's novel Gora was filmed with Nazrul as its music director and included one of his own songs. In June 1936, Sachin Sentupta’s important play, Shirajuddoula was staged. The songs and music were written and directed by Nazrul. The play and songs met with such unprecedented success that a gramophone recording was made, which at that time could be commonly heard in most households in Bengal.

In October 1939 Nazrul’s relationship with Kolkata Radio was formalized, and a large number of musical programmes were directly broadcast under his supervision. Worth mentioning are the critical and research oriented programmes such as “Haramoni” and “Noboragmalika”. From 1939 to 1942 (the time of his illness), the music programmes broadcast on radio are an important chapter in the history of Bengali music.

During 1939 different recording companies issued a total of over 1000 records, 1648 of which were Nazrul’s songs. The total number of his unrecorded songs is perhaps twice as much. Nazrul’s songs were broadcast also from Dhaka Radio. During 1939-40 the richness of the music programmes of Kolkata Radio deriving from Nazrul’s prolific creativity defies comparison. This trend continued throughout 1941, with songs based on many different ragas and narrative ballads. From 1939, when he first joined Calcutta Radio up to his illness in 1942, an extraordinary development of his music took place through countless radio programmes.

At the beginning of 1941 Sher-e-Bangla Fazlul Huq commenced re-publication of the daily newspaper Nobojug (“New Age”). Nazrul was its Chief Editor returning to the world of journalism at the final stage of his active life. Interestingly enough he had started his journalistic career at the "Nobojug”. It was while he was staying in the College Street office of the “Bengal Muslim Literary Society” that he began his literary journalistic career. His farewell speech at the silver jubilee anniversary of the Society at which he presided is probably the most significant and important speech he ever made. Entitled “If the flute plays no more” the speech is like a swansong in which he bids farewell to a sorrowful world.

Four months later, on August 8, 1941, Rabindranath Tagore died. Nazrul spontaneously composed two poems in Tagore’s memory, of which one was broadcast and recorded on gramophone. Within a year Nazrul himself fell seriously ill and gradually lost his power of speech. Thereafter from July 1942 to August 1976, the poet spent 34 years in silence.

Despite treatment Nazrul’s palsy and speech deficiency gradually increased. For the next 10 years his existence becoming gradually forgotten, though in 1945 he was awarded the “Jagattarini Gold medal” by Kolkata University. Then in 1952 he was transferred to the Ranchi Mental Hospital from where he was sent to London for treatment at the initiative of the “Nazrul Treatment Society”. Several eminent physicians in London including Sir William Sargent, were all of the opinion that his initial treatment had been inadequate and incomplete. Thereafter Nazrul was taken to Vienna where his condition was diagnosed as incurable. He and his family returned to India in December 1953. The rest of his life was spent in that condition. Earlier his wife had become ill in 1939 and though paralysed from the waist down, she spent the next 23 years of her life caring for her husband until her death at the age of 54 on 30 June 1962. At her wish she was buried at her husband’s birthplace, Churulia. Nazrul’s sons, Aniruddha died in 1974 at the age of 43, and Shabyashachi in 1979 at the age of 50.

After the liberation of Bangladesh, at the request of the Bangladesh Government the government of India agreed to allow Nazrul to be taken to reside in Bangladesh with his family. He arrived on 24 May 1972 as guest of the Government of Bangladesh and was accorded due honours. The President and Prime Minister paid their homage to him. In 1974 the Dhaka University awarded him the degree of Doctor of Literature. In 1976 the Government awarded him the “Ekushey Podok”. Bangladesh honoured itself by honouring Kazi Nazrul Islam as the national poet is Bangladesh with the citizenship of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

On 22 July 1975 Nazrul was transferred to the Post Graduate Hospital for continuous medical supervision. He spent the remaining one year, one month and eight days of his life there. On August 29, 1976 he breathed his last at 10:10 a.m.

As soon as Nazrul’s death was broadcast over Radio and T.V., the news spread like wild fire and plunged the Bengali nation in profound gloom. Life came to a standstill in Dhaka as thousands of men and women lined up to have a last glimpse of the rebel poet’s mortal remains in the Teacher-Students Centre of the University of Dhaka. Later at 5 p.m. the great poet was buried with full state honour.

This highly gifted poet’s writings explored themes such as freedom, humanity, love, and revolution. He opposed all forms of bigotry and fundamentalism, including religious, caste-based and gender-based. He wrote kirtans and bhajans along with ghazals and Haamd-Namath with equal depth.

As we celebrate the 125th birth anniversary of the rebel poet Kazi Nazrul Islam in 2024, we must recall Nazrul’s clarion call to embrace the spirit of universalism that rises above parochial pettiness and upholds the human dignity. His uncompromising attitude towards secularism never allowed any particular community to claim him and he continues to remain as an important symbol of unity among the Bengalis on both sides of the border.